Motivated reasoning is where we look for arguments in favor of conclusions we want to believe, regardless of the evidence. This is a primary stumbling block in forming sound beliefs and making good decisions. However, if we are science-curious, we are more likely to explore data contradicting our worldview and are less prone to this bias.

One of the significant cognitive biases we face in society is motivated reasoning. We tend to find arguments in favor of conclusions we want to believe to be stronger than arguments for findings we do not want to believe. Research shows that science-curious people are more likely to explore data contradicting their worldview and are thus less prone to this bias.

While many believe better education on the scientific method, evidence-based decision-making, and critical thinking will lead people to make more informed conclusions about complex topics like climate change, research reveals this is not always true. When presented with contradictory scientific data, a scientifically literate person may reinforce their existing beliefs rather than reassess them.Science curiosity is a desire to seek out and consume scientific information just for the pleasure of doing so.

People who are science-curious do this because they take satisfaction in seeing what science does to resolve mysteries.

That is different from somebody who would show interest in scientific information because they had a specific goal like wanting to do well in school.

Science-curious people are driven by the pure activity of consuming what science knows.

This phenomenon, known as motivated reasoning, is a cognitive bias where individuals utilize their knowledge and critical thinking to bolster justification for their preexisting views. Though counterintuitive, motivated reasoning demonstrates that greater scientific literacy does not necessarily equate to greater openness in evaluating one’s beliefs. This underscores the complexity of how we analyze information and the subconscious biases that shape our thinking.

However, research further shows that science-curious people are more likely to explore data contradicting their worldview and are less prone to motivated reasoning.

Curiosity

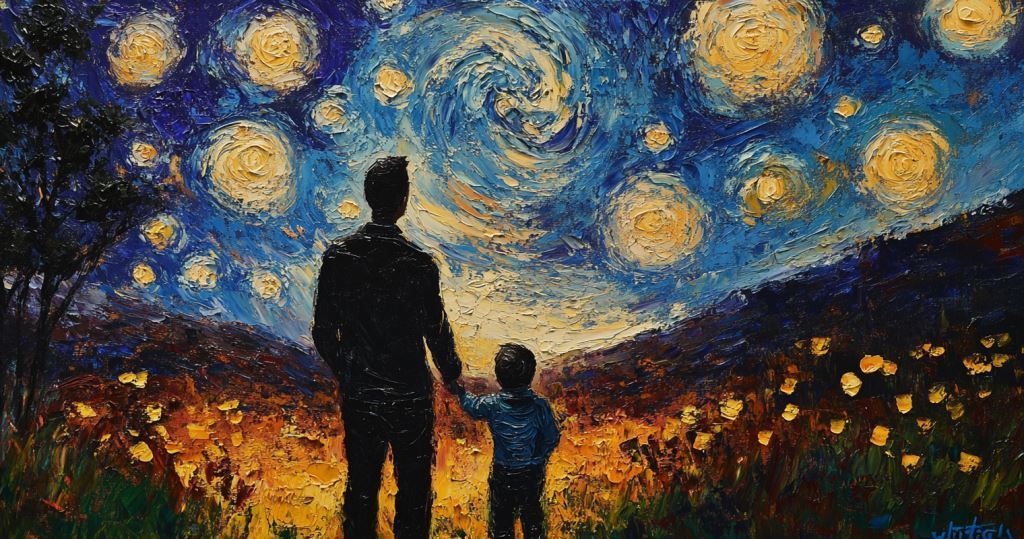

My father fought in the Second World War in North Africa and bivouacked in the desert under the stars of the night sky. One dark, cold winter night when I was about eight years old, he took me into the garden and showed me those stars, the constellations—the Great Bear, Orion, the Plough, and the great mass of stars spread across the sky—our home galaxy—the Milky Way.

My father fought in the Second World War in North Africa and bivouacked in the desert under the stars of the night sky. One dark, cold winter night when I was about eight years old, he took me into the garden and showed me those stars, the constellations—the Great Bear, Orion, the Plough, and the great mass of stars spread across the sky—our home galaxy—the Milky Way.

He told me that the stars were, in fact, suns like our sun, and they appeared small as they were so far away. He explained that scientists thought some of those suns might have planets like our Earth, and there could even be life on those planets.

Before we returned indoors, he said, "Wouldn't it be amazing if there were a father and son on one of those planets like us, looking up at the sky together and having a similar conversation?"

That winter evening, my father sowed the seed of curiosity in me about how the universe was created, who we were, where we came from, and why we are here. Awe, for the world and an intense curiosity about it have lived within me ever since. Thank you, Dad.

I developed a passion for science and studied physics. In my early career, I worked in the aerospace industry. Although I long ago moved on, one of the things that has stayed with me is my love for science and, in particular, the scientific method—the way in which we make sense of the world.

Nothing delights me more than when some scientific discovery or insight usurps a long-cherished belief. These overturns in thinking are how we make progress.

The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled.

What’s the significance of the above story? As young children, we are born curious about the world. It’s a natural human trait.

Still, our education system methodically suppresses curiosity so that by the time we reach adulthood, little wonder about the world remains. I was lucky to have a father who lit a small fire in me that never died.

The challenge for the education system is not to educate more scientists, although that is a worthy end in itself, but to ensure that everyone understands the scientific method and remains science-curious throughout life.

Progress and democracy depend on it.

Earth’s Rotation Visualized in a Timelapse of the Milky Way Galaxy | Aryeh Nirenberg

This visualization of the Earth rotating against the fixed backdrop of our galaxy is stunningly beautiful. It fills me with awe, and I come close to tears every time I watch it.

A boy can take you into the open at night and show you the stars; he might tell you no end of things about them, conceivably all that an astronomer could teach.

But until and unless he feels the vast indifference of the universe to his own fate, and has placed himself in the perspective of cold and illimitable space, he has not looked maturely at the heavens.

Until he has felt this, and unless he can endure this, he remains a child, and in his childishness, he will resent the heavens when they are not accommodating.

He will demand sunshine when he wishes to play, and rain when the ground is dry, and he will look upon storms as anger directed at him, and the thunder as a personal threat.

Scout Mindset

An alternative term for science-curiosity, given to it by Julia Galef, is scout mindset.

Why you think you’re right – even if you’re wrong | Julia Galef (source)

Perspective is everything, especially when it comes to examining your beliefs. Are you a soldier, prone to defending your viewpoint at all costs — or a scout, spurred by curiosity? Julia Galef examines the motivations behind these two mindsets and how they shape the way we interpret information, interweaved with a compelling history lesson from 19th-century France ![]() .

.

She then goes on to explain the concept of motivated reasoning ![]() :

:

Finally, when your steadfast opinions are tested, Julia asks ![]() :

:

“What do you most yearn for?

Do you yearn to defend your own beliefs or do you yearn to see the world as clearly as you possibly can?”

Science curiosity is not an easy habit to develop, but it is crucial to practice Conversational Leadership more effectively.

Resources

- Ars Technica: “Science curious” more likely to explore data contradicting their world view by Scott K. Johnson

- Scientific American Blog Post: Why Smart People Are Vulnerable to Putting Tribe Before Truth by Dan Kahan

Posts that link to this post

- Introduction: Knowledge Delusion We delude ourselves about what we know and how we make decisions

- Trust & Belief Formation Trust plays a critical role in forming our beliefs

POST NAVIGATION

CHAPTER NAVIGATION

Tags: cognitive bias (28) | critical thinking (49) | curiosity (27) | Dan Kahan (9) | democracy (37) | education (25) | Julia Galef (6) | mindset (14) | motivated reasoning (14) | science (23) | science curiosity (9) | science literacy (2) | scientific method (27)

SEARCH

Blook SearchGoogle Web Search

Photo Credits: Greg Rakozy (Unsplash)

If you enjoy my work and find it valuable, please consider giving me a little support. Your donation will help cover some of my website hosting expenses.

Make a donation