Disagree constructively: Disagreement is an inevitable part of life. Most of the time, we do it poorly. We need to learn to disagree constructively. How do we go about it? A simple disagreement hierarchy provides guidance.

Disagreement is an inevitable part of life. But unfortunately, we mostly do it poorly. Paul Graham’s disagreement hierarchy provides a structure for doing it respectfully and more effectively.

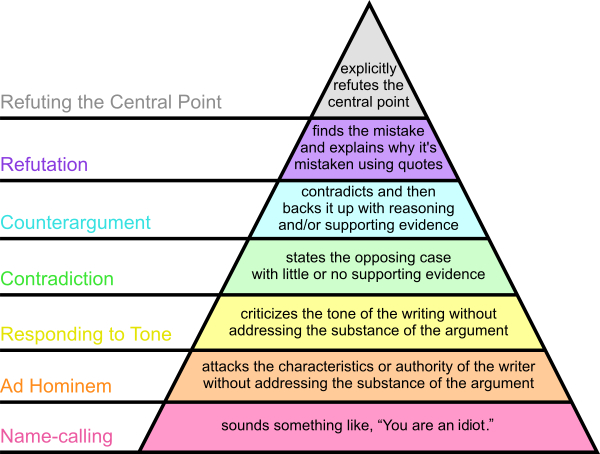

Paul Graham’s Disagreement Hierarchy

The web is turning writing into a conversation. Twenty years ago, writers wrote and readers read. The web lets readers respond, and increasingly they do—in comment threads, on forums, and in their own blog posts.

Many who respond to something disagree with it. That’s to be expected. Agreeing tends to motivate people less than disagreeing. And when you agree there’s less to say. You could expand on something the author said, but he has probably already explored the most interesting implications. When you disagree you’re entering territory he may not have explored.

The result is there’s a lot more disagreeing going on, especially measured by the word. That doesn’t mean people are getting angrier. The structural change in the way we communicate is enough to account for it. But though it’s not anger that’s driving the increase in disagreement, there’s a danger that the increase in disagreement will make people angrier. Particularly online, where it’s easy to say things you’d never say face to face.

If we’re all going to be disagreeing more, we should be careful to do it well. What does it mean to disagree well? Most readers can tell the difference between mere name-calling and a carefully reasoned refutation, but I think it would help to put names on the intermediate stages. So here’s an attempt at a disagreement hierarchy:

Credit: How to disagree by Paul Graham

The hierarchy of disagreement is a concept proposed by Paul Graham in his 2008 essay How to Disagree. His hierarchy has seven levels, from “Name-calling” to “Refuting the central point”.

- Name-calling. This is the lowest form of disagreement and probably also the most common.

- Ad Hominem. An ad hominem attack is not quite as weak as mere name-calling.

- Responding to Tone. At the next level up, we start to see responses to the writing rather than the writer.

- Contradiction. In this stage, we finally get responses to what was said, rather than how or by whom.

- Counterargument. At this level, we reach the first form of convincing disagreement: counterargument.

- Refutation. The most convincing form of disagreement is a refutation.

- Refuting the Central Point. The force of a refutation depends on what you refute. Thus, the most powerful form of disagreement is to refute someone’s central point.

How to have constructive conversations | Julia Dhar (source)Productive disagreement depends on how people feel about each other.

We spend a lot of time thinking about how to argue, and not enough on how to shape the relationship that will define how the engagement goes.

It’s often said that in order to disagree well, people need to put emotions aside and think purely rationally, but this is a myth.

Disagreeing productively requires a bond of trust: a sense that we are ultimately working with, and not against, each other.

That's an inherently emotional question as well as a cognitive one ...

People are not purely rational, and acting as if they are leads to dysfunction.

We release the full potential of this disagreement when we incorporate our unreasonableness into the process.

Love Your Enemies — Disagree Better, Not Less | Arthur Brooks (source)

Imagine a culture where an argument is viewed as a dance, the participants are seen as performers, and the goal is to perform in a balanced and aesthetically pleasing way.

In such a culture, people would view arguments differently, experience them differently, carry them out differently, and talk about them differently.

But we would probably not view them as arguing at all: they would simply be doing something different.

It would seem strange even to call what they were doing "arguing."

Perhaps the most neutral way of describing this difference between their culture and ours would be to say that we have a discourse form structured in terms of battle and they have one structured in terms of dance.

We need to learn to disagree constructively. Paul Graham’s disagreement hierarchy provides a structure for doing it respectfully and more effectively.

Posts that link to this post

- Conversation Covenant Creating a psychologically safer space for difficult conversations

- Discrediting People ** Cause them to lose the respect or trust of others

- Opinion Polarization We are polarized across political, religious, moral, and racial divides

- Show Respect Failing to respect one another negatively impacts the future for all of us

POST NAVIGATION

CHAPTER NAVIGATION

Tags: argument (33) | constructive disagreement (17) | conversation covenant (6) | debate (23) | dialogue (68) | disagreement (12) | discussion (2) | impossible conversations (16) | Paul Graham (1) | respect (24) | social reasoning (19)

SEARCH

Blook SearchGoogle Web Search

Photo Credits: Midjourney (Public Domain)

The Gurteen Knowledge Letter is a free monthly newsletter with over 20,000 subscribers that I have been publishing by email for over 20 years.

Learn more about the newsletter and register here.