Societies often assume that virtue leads to prosperity, but history suggests a more complex reality. Efforts to eliminate self-interest can unintentionally suppress growth and innovation. Recognizing the role of competition, ambition, and even conflict in progress can lead to more effective leadership and a deeper understanding of human dynamics.

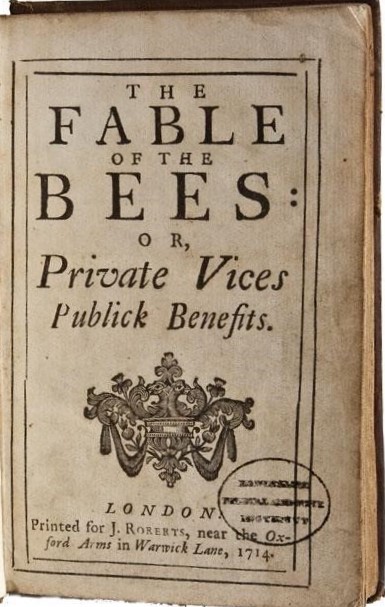

The Fable of the Bees: Or, Private Vices, Public Benefits is a satirical poem by Bernard Mandeville, first published in 1705 and later expanded in 1714. The work uses the allegory of a thriving beehive to explore the paradox that individual self-interest and even morally questionable behaviors can unintentionally contribute to societal prosperity.

The Allegory of the Beehive

In the poem, the bees live in a bustling, prosperous hive, where every bee engages in self-serving activities driven by vanity, greed, and ambition. Despite—or rather because of—these private vices, the hive flourishes with economic growth, innovation, and cultural richness. However, the hive’s economy collapses when the bees suddenly embrace virtue, becoming honest and morally upright. The absence of selfish desires leads to stagnation, unemployment, and decline, ultimately reducing the once-vibrant society to a simple, humble existence.

The Fable of the Bees | Bernard Mandeville

In the poem, the bees live in a bustling, prosperous hive, where every bee engages in self-serving activities driven by vanity, greed, and ambition. Despite—or rather because of—these private vices, the hive flourishes with economic growth, innovation, and cultural richness. However, the hive’s economy collapses when the bees suddenly embrace virtue, becoming honest and morally upright. The absence of selfish desires leads to stagnation, unemployment, and decline, ultimately reducing the once-vibrant society to a simple, humble existence.

The Fable of the Bees | Bernard MandevilleThe bees in this hive had doctors, lawyers, merchants, and artisans, all of whom played a role in the society. Some professions thrived on the misfortunes of others—doctors earned money from sickness, lawyers profited from lawsuits, and soldiers found purpose in conflict. The hive’s prosperity depended on competition, ambition, and even a bit of dishonesty.

One day, however, some of the bees began to complain. They wished for a society based on honesty, virtue, and fairness. They believed that the hive would be even better if everyone behaved morally. They prayed for honesty to replace deceit, justice to remove corruption, and modesty to replace greed.

To their surprise, their wish was granted. The dishonest merchants became honest, the corrupt politicians reformed, and the lawyers no longer took advantage of disputes. As people stopped seeking personal gain at the expense of others, industries that once thrived on human weakness began to shrink. The economy slowed, jobs disappeared, and the once-prosperous hive began collapsing.

Without greed and ambition, there was no drive for innovation. Without the need for self-defense, the soldiers were no longer needed. With honesty prevailing, there were fewer lawsuits, and the lawyers became idle. Once a powerful and wealthy society, the hive became weak and inefficient.

Ultimately, the bees who had wished for virtue realized their mistake. Their society had thrived not despite human flaws but because of them. When ambition, competition, and even a little dishonesty were part of the system, everyone had work, and the hive was prosperous.

The story’s moral is that prosperity often depends on self-interest, even if it comes with flaws. A society that seeks to eliminate all vices may also remove the very forces that drive progress and wealth.

The original poem, “The Grumbling Hive: or, Knaves Turn’d Honest,” which forms the core of The Fable of the Bees, was written in rhymed couplets and serves as a satirical allegory about how self-interest and even vices contribute to economic prosperity.

The original poem, “The Grumbling Hive: or, Knaves Turn’d Honest,” which forms the core of The Fable of the Bees, was written in rhymed couplets and serves as a satirical allegory about how self-interest and even vices contribute to economic prosperity.

Mandeville later expanded on the ideas in the poem through explanations, adding essays and commentary that turned The Fable of the Bees into a full-fledged philosophical work. The book itself, including these expansions, is much longer and includes discussions on morality, economics, and human nature.

Mandeville’s Controversial Argument

This idea parallels themes found in The Fable of the Bees, though Smith took a different approach, emphasizing competition and market efficiency over moral arguments. Both recognized that self-interest can be a powerful force for economic and social progress.

His core argument—that private vices such as greed and vanity can drive public prosperity—disrupts conventional thinking and raises an ongoing tension: Can society thrive purely on virtue, or do self-interest and morally ambiguous behaviors play a crucial role?

From an economic perspective, Mandeville anticipates capitalism’s dynamic and often chaotic nature. Markets flourish through competition, ambition, and sometimes excess. The idea that consumerism, luxury, and financial speculation fuel economic growth aligns with modern economic thought, demonstrating Mandeville’s forward-thinking approach.

However, his argument sparked significant controversy, as the notion that vice is essential for progress is not without flaws. While self-interest can drive innovation and prosperity, unchecked greed and corruption can lead to inequality and instability. The challenge lies in balancing individual ambition with ethical governance and social cohesion.

However, much like The Fable of the Bees, Asimov’s story reveals a paradox: the very efforts to eliminate risk, conflict, and upheaval also suppress humanity’s potential for growth, creativity, and exploration. By erasing the challenges that drive innovation, the Eternals inadvertently stunt human progress, particularly the ambition to reach the stars. The novel’s central conflict arises when one of the Eternals, Andrew Harlan, questions whether this controlled “perfection” is genuinely beneficial or if humanity’s messier, risk-filled history would ultimately lead to greater achievements.

Conversational Leadership and the Lessons of The Fable of the Bees

Mandeville’s The Fable of the Bees offers a compelling perspective on the complexities of human nature, self-interest, and societal progress—ideas that have strong parallels with Conversational Leadership. At its core, Conversational Leadership embraces the power of dialogue to navigate ambiguity, challenge assumptions, and harness diverse perspectives to drive meaningful change.One of the greatest reasons why so few people understand themselves, is, that most writers are always teaching men what they should be, and hardly ever trouble their heads with telling them what they really are.

Just as Mandeville argues that seemingly undesirable traits like ambition and competition can lead to economic growth, effective leadership recognizes that productive conversations often emerge from tension, differing viewpoints, and even conflict. Those who foster open, honest, and sometimes uncomfortable discussions can create an environment where innovation and progress thrive.

Moreover, The Fable of the Bees reminds us that practicing leadership is not about enforcing an idealized vision of harmony but engaging with human behavior’s fundamental, often messy, dynamics. Just as societies must find a balance between virtue and self-interest, Conversational Leadership requires navigating between structure and adaptability, control and emergence, vision and improvisation.

Ultimately, both Mandeville’s insights and Conversational Leadership highlight that progress is not about eliminating imperfection but understanding and working with the natural complexities of human interactions.

Immorality—acts such as lying, cheating, stealing, and even killing—is not an aberration but a potential aspect of our nature, shaped by evolutionary pressures alongside virtues like cooperation, trust, and fairness. While we are capable of vice, we are equally capable of moral behavior, and both tendencies have been essential for human survival. Within our own tribe—our close social group, family, or community—we tend to favor fairness and reciprocity, as strong social bonds enhance collective well-being. However, history and psychology suggest that our moral instincts can shift depending on context, sometimes leading to self-serving behaviors when dealing with those outside our immediate group. Yet this is not a rigid law; societies have long developed institutions, cultural norms, and ethical frameworks to extend cooperation beyond tribal boundaries.

If we accept these premises, we must ask: What does this tell us about the challenge of creating a better world? If immorality is not simply a matter of individual failure but is a recurring feature of human nature, what strategies should we adopt? Should we seek to suppress these instincts, redirect them, or structure society in ways that channel them toward productive ends?

This brings us to The Fable of the Bees and Bernard Mandeville’s provocative argument that private vices can lead to public benefits. While Mandeville suggested that self-interest—when properly directed—can drive economic and social progress, he did not argue that all immoral behaviors contribute positively to society. Adam Smith, for example, built on this idea by distinguishing between self-interest that fuels productivity and destructive behaviors that undermine trust. If some degree of self-interest is inevitable, how do we design social, economic, and political systems that encourage beneficial forms while curbing those that lead to harm?

Rather than beginning with moral idealism or cynicism, this line of thinking challenges us to take a pragmatic approach: acknowledging human nature while recognizing that morality is not static. Ethical progress has never been about simply suppressing vice; it has also involved fostering the conditions under which cooperation, fairness, and trust can thrive. The question, then, is not just how we can make people more virtuous but how we can build systems that incentivize ethical behavior while managing the more self-serving aspects of human nature.

Understanding the balance between self-interest and social good is key to effective leadership and decision-making. Instead of eliminating tension and conflict, engage with them productively. Encourage honest conversations, recognize diverse motivations, and create systems that channel ambition into positive outcomes. Progress comes from working with human nature, not against it.

Resources

POST NAVIGATION

CHAPTER NAVIGATION

Tags: Adam Smith (2) | Bernard Mandeville (4) | Isaac Asimov (2) | morality (10) | society (7) | virtue (1)

SEARCH

Blook SearchGoogle Web Search

Photo Credits: Midjourney ()

Conversational Leadership is the practice of creating space for what needs to be said. Coaching helps you develop this capacity in real, grounded ways.